Noted Cellist and Flutist to Perform with MCC Faculty Member for “World of Music” Concert

As part of the Fall 2024 “A World of Music” concert series, Middlesex Community College will present Duos and Trios Featuring Cello, Piano and Flute. The concert will take place at 3 p.m. on Sunday, October 6 at MCC’s Concert Hall in Bedford.

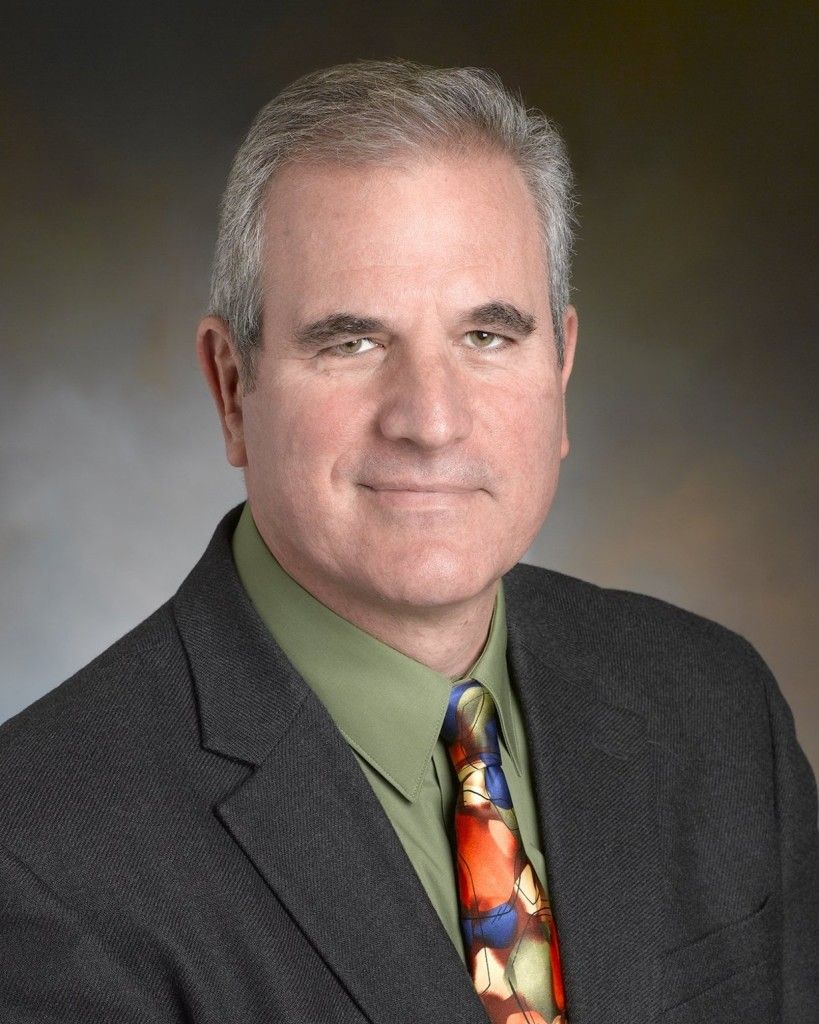

“Our exciting and varied program features cellist Jesús Castro-Balbi and flutist Jill Dreeben, who are wonderful musicians and friends of mine,” said Carmen Rodríguez-Peralta, pianist, and MCC Chair of Music. “Both have played with me previously at MCC, but this is the first time that we will be performing together.”

During the program, colorful works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Arthur Foote, Larry Bell, Claude Debussy and Gaspar Cassadó will be performed by Rodríguez-Peralta, Castro-Balbi and Dreeben.

“I am thrilled to be performing Larry Bell's new piece Serenade No. 6 for flute, cello and piano with my good friends at MCC,” Dreeben said. “We will be playing the classic flute Sonata in E-major by JS Bach, my favorite composer!”

“I so look forward to returning to MCC and joining my fabulous artist colleagues in a program exploring colorful and engaging music ranging from time-tested favorites to Larry Bell’s exciting new Serenade,” Castro-Balbi said.

This Fall, other concerts held in the Bedford Concert Hall include Afro-Brazilian Music with Marcus Santos at 11 a.m. on Tuesday, October 22 and a Student Recital at 12:30 p.m. on Monday, December 2.

“A World of Music” will also feature performances at the Richard and Nancy Donahue and Family Academic Arts Center in Lowell. This includes Phantom of the Opera with Live Music at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 17 and the Lowell Chamber Orchestra at 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, November 23.

A previous performance from the Lowell Chamber Orchestra kicked off the Fall season on Sunday, September 8.

All concerts are free and open to the public.

MCC’s Concert Hall is located in Henderson Hall at 591 Springs Road in Bedford. Parking is available on-campus. Visit www.middlesex.mass.edu/worldofmusic/ for more information

“Our exciting and varied program features cellist Jesús Castro-Balbi and flutist Jill Dreeben, who are wonderful musicians and friends of mine,” said Carmen Rodríguez-Peralta, pianist, and MCC Chair of Music. “Both have played with me previously at MCC, but this is the first time that we will be performing together.”

During the program, colorful works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Arthur Foote, Larry Bell, Claude Debussy and Gaspar Cassadó will be performed by Rodríguez-Peralta, Castro-Balbi and Dreeben.

“I am thrilled to be performing Larry Bell's new piece Serenade No. 6 for flute, cello and piano with my good friends at MCC,” Dreeben said. “We will be playing the classic flute Sonata in E-major by JS Bach, my favorite composer!”

“I so look forward to returning to MCC and joining my fabulous artist colleagues in a program exploring colorful and engaging music ranging from time-tested favorites to Larry Bell’s exciting new Serenade,” Castro-Balbi said.

This Fall, other concerts held in the Bedford Concert Hall include Afro-Brazilian Music with Marcus Santos at 11 a.m. on Tuesday, October 22 and a Student Recital at 12:30 p.m. on Monday, December 2.

“A World of Music” will also feature performances at the Richard and Nancy Donahue and Family Academic Arts Center in Lowell. This includes Phantom of the Opera with Live Music at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 17 and the Lowell Chamber Orchestra at 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, November 23.

A previous performance from the Lowell Chamber Orchestra kicked off the Fall season on Sunday, September 8.

All concerts are free and open to the public.

MCC’s Concert Hall is located in Henderson Hall at 591 Springs Road in Bedford. Parking is available on-campus. Visit www.middlesex.mass.edu/worldofmusic/ for more information